Point of view (POV) can make or break your story. Finding the right POV requires knowledge of the different kinds of POV and how they work. And then, when you’ve picked a POV, you need to work hard to keep it consistent.

But once you learn the basics, all it takes is practice.

Keep reading to learn what point of view is, which varieties exist, and how to manage them.

What is point of view (POV)?

Point of view (POV) refers to the perspective from which a story is told – who is narrating the story and how much information the reader gets access to.

It’s important to distinguish between the narrator and the viewpoint character. The narrator is the person telling us the story. The viewpoint character is the person experiencing the story.

Imagine that the narrator is a ghost, a disembodied spirit who can move around the world, hovering above it or diving close. The ghost has an incredible ability to slide into a person’s mind and experience the world as that person experiences it. That’s the power of the narrator.

But the ghost’s powers are usually limited. Let’s look at how a narrator’s powers are most often limited by point of view.

Omniscient narrator

An omniscient (“all knowing”) narrator – a god-like ghost – has the most freedom. It can fly high above the action and then zoom down into the mind of a character. After a while, it can jump out of that character and enter another character’s mind. It can also comment on the bigger picture, with insights into characters that would be impossible for, say, a journalist to know.

If you’ve read Charles Dickens or Leo Tolstoy – and other 19th century novelists – you may recognize this technique. But it also appears in more recent books, like Ann Patchett’s Bel Canto.

“Everything was in confusion in the Oblonskys’ house. The wife had discovered that the husband was carrying on an intrigue with a French girl, who had been a governess in their family, and she had announced to her husband that she could not go on living in the same house with him. This position of affairs had now lasted three days, and not only the husband and wife themselves, but all the members of their family and household, were painfully conscious of it. Every person in the house felt that there was no sense in their living together, and that the stray people brought together by chance in any inn had more in common with one another than they, the members of the family and household of the Oblonskys.”

The key effects of omniscient narration – and the risks:

- Provide a big picture view: The narrator has the freedom to provide a big picture view of a story that involves many characters across many locations – and even across a long time period. This is useful if you’re telling a story about a community that spans a long time. The risk with this freedom is that you may lose focus. With so many places to go, so much to see, what should you focus on? The reader may get lost and lose the connection with the essence of the story.

- Comment on the story: The narrator can assume a “storyteller” voice, commenting on the action and offering information that none of the characters would know. We all know the storyteller from fairy tales: “Once upon a time…” The risk of omniscient commentary is that the narrator becomes so “intrusive” that the reader feels the author is interrupting the story to comment. Too much of this interruption feels like being “talked at” by the author, alienating the reader from the story itself.

- Contrast characters’ experiences: The narrator can show how several characters in a single scene view the situation, slipping in and out of their viewpoints and commenting on the action. The risk is “head hopping” – when the narrator makes abrupt leaps from one viewpoint to another, confusing or alienating the reader.

Third-person limited

With third-person limited, the narrator is not a character in the story. You’ll recognize this as the classic “she walks down the street” story.

Although “she walks down the street” sounds like the narrator sees the character at a distance, the limitation is this: the narrator refers to the character from the outside but focuses exclusively on that character’s thoughts, feelings, and perceptions. Usually, the narrator doesn’t reveal information about the character that the character herself wouldn’t know.

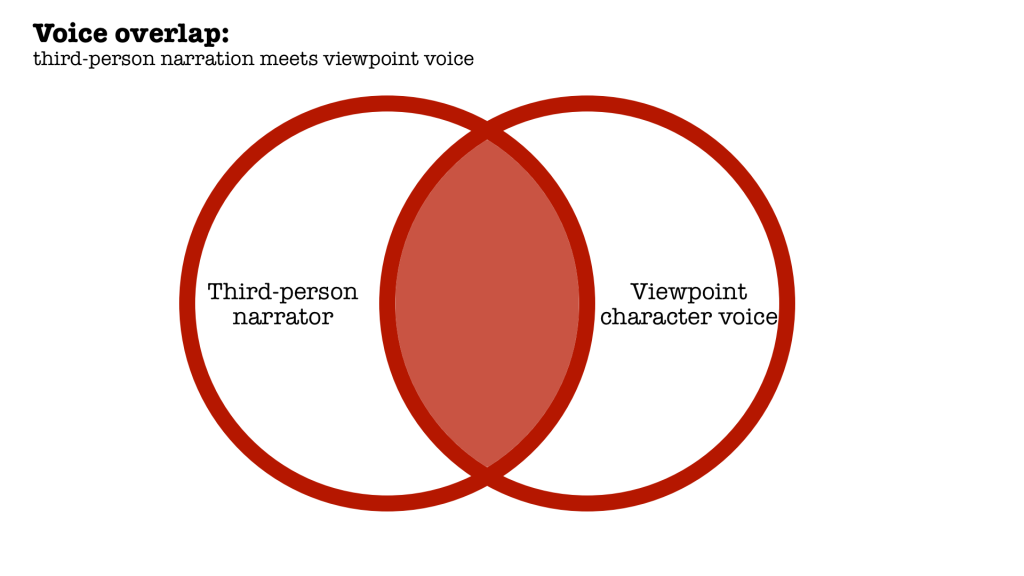

This hybrid approach also creates a fusion of voices. The closer the narrator gets to the character, the more the narrator’s voice sounds like the character’s own voice. It’s as if we get a hybrid of the third-person narrator and a first-person voice.

But this doesn’t mean that the writer must stick with just one character for an entire novel. Usually, readers expect a scene to be told from one viewpoint character’s perspective. But in the next scene, the narrator may shift to another viewpoint character, fusing with that person’s voice.

If the narrator makes this shift from one character to another, it usually happens with a clear break in the narrative – such as after a scene break or when a new chapter begins. Sometimes that’s called a “multiple point of view” narrative.

“When Helen woke again, Hugh and Manus were sound asleep. It was just after eight o’clock; the room was hot. She slipped out of the bed and, carrying her dressing-gown and slippers, she went downstairs, where she found Cathal, still in his pyjamas, watching television, the zapper in his hand.”

The key effects of third-person limited – and the risks:

- Readers can relate to the viewpoint character: The closeness to the viewpoint character establishes a bond between the reader and the character, potentially increasing the reader’s involvement. But you can’t show the contrasting thoughts of other characters in a scene (otherwise it’s omniscience), so that means you have to maintain strict control of the narrative viewpoint.

- The novel’s tone can exist on two levels: With the viewpoint character’s voice coloring the narrative, you can play with two voices. For example, the narrator can use language that suggests a dark, brooding story, even as the viewpoint character’s own voice is light and carefree. This contrast can make the reader worry. Obviously, the dark, brooding world is a threat; will the viewpoint character realize it before danger strikes? Another example: In a story about depression, you can begin with a “neutral” narrative voice; then, as the story progresses and the viewpoint character becomes more and more depressed, the narrative voice can take on more and more of that brooding quality. The risk here is that the writer needs to manage two distinct voices and, in this last example, even create a seamless evolution of that voice to dramatize the character’s worsening depression.

First-person

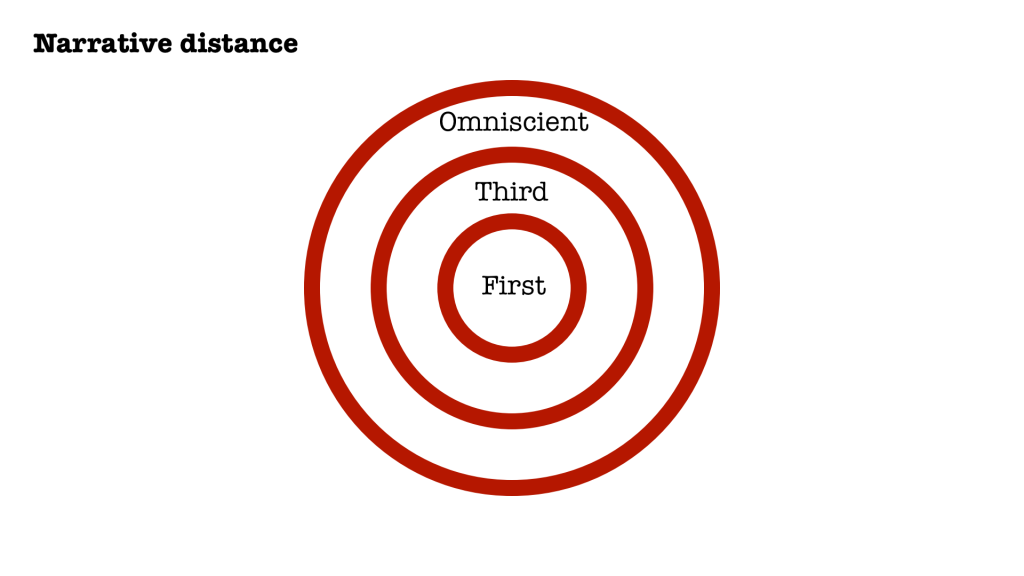

The first-person narrator is the most limited of them all. Here, the narrator merges with the viewpoint character. The “ghost” cannot escape the character’s interior. What the character sees, the narrator describes: “I walked down the street…”

This approach limits the reader’s knowledge of the story world to the viewpoint character’s thoughts, feelings, and perceptions.

“Branshaw Manor lies in a little hollow with lawns across it and pine-woods on the fringe of the dip. The immense wind, coming from across the forest, roared overhead. But the view from the window was perfectly quiet and grey. Not a thing stirred, except a couple of rabbits on the extreme edge of the lawn. It was Leonora’s own little study that we were in and we were waiting for the tea to be brought. I, as I said, was sitting in the deep chair, Leonora was standing in the window twirling the wooden acorn at the end of the window-blind cord desultorily round and round. She looked across the lawn and said, as far as I can remember: ‘Edward has been dead only ten days and yet there are rabbits on the lawn.’”

The key effects of first-person narration – and the risks:

- Create a powerful intimacy: No other narrative form can create such a sense of intimacy between the viewpoint character and the reader. As a reader, you feel you’re living the story vicariously through the narrator. The lack of narrative distance makes the story feel immediate. The downside is that you are so close to the character that the experience can feel small, limiting, even claustrophobic. This works well for a novel that’s exploring a character’s state of mind, but it’s hard to pull off for a giant, sweeping saga covering many locations, many characters, and an extended time period.

- Emphasize the power of voice: Some of the most compelling first-person stories grab us because the character’s unique voice hooks us. Mark Twain’s Huckleberry Finn, Per Petterson’s Trond Sander in Out Stealing Horses, and Alice Walker’s Celie in The Color Purple – these viewpoint characters all speak with distinctive voices. The risk is that your story offers lots of voice but no substance: nothing happens. Or that the voice is dull or inconsistent, alienating the reader from the story.

- Establish reliability or unreliability: A confident first-person narrator can be a joy to read. But sometimes that narrator can’t be trusted. When the story kicks off, we may believe we’re being told the truth, only to discover that things don’t add up. Gradually, we suspect the narrator isn’t telling the entire truth – either lying to us or lying to themselves about the reality of their situation. This is called an unreliable narrator. A beautiful example is the butler, Stevens, in The Remains of the Day by Kazuo Ishiguro. But this technique can be difficult to pull off, and there’s a risk that the reader feels manipulated.

I’ve heard people say that first-person narratives are “simplistic” or “too limiting” – even that “serious writers” aspire to stick to the third-person. That’s silly. The first-person narrator can cover a lot of ground, not least creating an intimate engagement with the reader.

But if you want to experiment with narrative form, the first person also offers a variety of approaches:

- Stream of consciousness

- Confession or remembrance (e.g. a mature narrator looking back on something that happened when he was younger and less experienced)

- Letters (e.g. an epistolary novel, like the letters and diary entries in Dracula)

- Nested stories (e.g. where a first-person narrator tells a story, also told by a first-person narrator, creating an additional layer – see A Heart of Darkness by Joseph Conrad or The Turn of the Screw by Henry James)

You can also choose to tell a first-person story in a plural voice: we/us. This is unusual, so you don’t see it often – and especially not in genre fiction. But it can be a compelling way to tell a story about a collective experience.

Joshua Ferris uses the first-person plural in his advertising agency satire, Then We Came to the End. But you can also mix the first-person singular with the plural, as Carsten Jensen does in his novel, We, the Drowned – giving a voice to the seafaring community he chronicles, while also allowing the narrative to dive into first-person singular voices.

Second-person

The first-person plural isn’t the only unorthodox approach to narrative. In a second-person story, the narrator addresses the reader directly as the viewpoint character. You’re the protagonist.

This works well for choose-your-adventure books, but for fiction it’s rarely used. Jay McInerney used it in his 1984 novel, Bright Lights, Big City, but I’ve mostly seen it used in short stories, where the technique is short-lived. For example, Lorrie Moore has a story called “How to Become a Writer,” which lampoons self-help books – a fitting use of the second-person narrator.

“Decide that you like college life. In your dorm you meet many nice people. Some are smarter than you. And some, you notice, are dumber than you. You will continue, unfortunately, to view the world in exactly these terms for the rest of your life.”

The key effects of second-person narration – and the risks:

- Surprise the reader with an unconventional approach: Most readers expect a first-person or third-person narrative, so when a story addresses them as the viewpoint character, it can be a delightful surprise. It’s a format that can work well for comedy. But it’s also difficult to sustain over many pages.

- Create an uncomfortable immediacy: By casting the reader as the viewpoint character, you’re making them the protagonist, as if they’d entered a video game. When the story puts the viewpoint character in uncomfortable situations that are relatable, this can make the reader squirm. The risk, of course, is that the situations aren’t relatable, and then the reader might feel alienated from the story.

A note on power and control

The more freedom you have as a narrator, the more control you need to have over the story. You might think the freedom of omniscience is ideal. You can do anything! And so you can. But can you do it well?

With omniscience, you can easily make a mess of a story. Your job becomes to impose strict control over your narrative to ensure that readers feel you’ve made just the right choices at the right time.

In contrast, the first-person narrative has strict control baked into the format. There are strict boundaries – defined by what the single viewpoint character whose psyche and voice the narrator inhabits – and the writer’s job is to tell a story within those boundaries.

That’s why I usually recommend that novice writers start with first-person or third-person limited narratives, where predefined boundaries set helpful limitations on the story. You shouldn’t see these limitations as negative – the constraints we set on our writing can heighten our creativity and lead to unexpected originality.

How do I choose the right POV for my story?

Sometimes the best POV for the story you want to tell will be obvious. As soon as you have an idea, you see that the story you want to tell and the effects you want to create suggest, say, a first-person narrative. Other times, you need to think through the story before settling on a particular POV.

When you’re selecting your POV, consider the following:

- Commercial genre: Certain commercial genres rely on a particular POV. For example, cozy mysteries typically use first-person or third-person limited POV, with the sleuth as the POV character. In contrast, an epic fantasy will often be told in a third-person multi-viewpoint narrative style, providing the breadth the story needs to unfold across a big canvas.

- Information control: How much do you want your reader to know? In a murder mystery, information control is essential. But most stories are about a mystery of some kind (e.g. what secret did the father leave behind when he emigrated, who’s going to win the pie-eating contest, or which of the sisters will marry the handsome stranger?).

- Story canvas: How big is your canvas? How focused should your story be? Stories that focus on 1-3 individual characters’ experiences often rely on a limited point of view: first person or third-person limited. Likewise, if you want to create a strong sense of intimacy – for example, in a story that has much more internal conflict than external conflict. But if you’re telling an epic historical narrative spanning the two world wars and involving a cast of dozens, you’re likely to choose a multi-viewpoint third-person or even omniscient narrative.

- Voice: If your story depends on a strong sense of place, you may want the viewpoint character’s voice up front. In third-person limited, the viewpoint character’s speech mannerisms can color the narrative. Or you may opt for a first-person narrator to give the character full control of the story’s speech.

Sometimes a story idea can fit into any kind of POV, and then it’s difficult to choose. Whenever I’ve had a hard time deciding, I’ve found the exercise below helpful.

Exercise: discovering the best POV

- Pick three scenes from the story. Don’t worry if you’re not sure if these scenes will actually occur. So long as they feel like scenes that might occur.

- Choose a POV. Most often, this will be first person or third person. Which means you will now write six scenes – three using a first-person POV and three using the third-person POV.

- Set a timer and write for 10 minutes. You’ll free write in your chosen POV narrative for 10 minutes, working your way into the scene. Don’t worry about grammar or style. Don’t worry about whether the characters are true to your original idea. This is an exercise – not the final version you’ll include in your novel. The most important thing is that you start writing and keep it up until the timer goes off.

- Set the draft aside and start another, continuing until you’ve finished your six drafts. Once you’ve done all your drafts (and you can choose to do more than the six I suggested, if you want), look them over and identify how the POV works. Is one more appropriate for information control? Does one work better for the story canvas size? And what about voice – do you feel one POV suits your story better than another?

Beware of these common POV pitfalls

- Head-hopping: If you switch between characters’ POVs within a single scene or chapter, you can confuse the reader and disrupt the flow of the narrative. Even in omniscient narration, where POV switches are more common, a sudden shift can cause problems. Because omniscient narration was more popular in the past, you’ll read classics where head hopping happens – and it may work well in the hands of a 19th century novelist. But today, audiences are wary of head hopping, and inconsistency can appear amateurish.

- Using POV inconsistently: Be careful you don’t shift from one type of POV to another without a logical reason or a smooth transition. For example, in a third-person limited narrative, you may slip into omniscience and then return to a limited POV in the rest of the chapter. As with head hopping, this can create a disjointed narrative that confuses the reader.

- Controlling narrative distance: Usually, when a scene calls for the reader to get some insight into the viewpoint character’s feelings or thoughts, it’s time for the POV to slide close to the character. Make sure you don’t have emotionally powerful scenes where the reader gets access to the viewpoint character’s thoughts and feelings and then other, similarly powerful scenes where they don’t. The reader will feel cheated that they didn’t get to experience the character’s reactions. And they may also feel that the narrative is inconsistent, and that can pull them out of the story experience.

- Using voice inconsistently: It’s hard to establish a viewpoint character’s voice and then stick with it. With a first-person narrator, ask yourself, “Would she really say that?” With a third-person narrator, you need to ask the same question, while also checking where the “neutral” narrator occurs and where the viewpoint character’s voice shines through. Usually, this will happen as the third-person narrator slides closer to the viewpoint character’s perspective.

- Telling instead of showing: This isn’t a problem exclusive to POV. In fact, it’s so common that it’s worth mentioning (and mentioning again and again). When you’re telling instead of showing the story’s action, you summarize events or characters’ thoughts and feelings. For actions that are important to the story’s development, you’ll mostly want to show what happens. Allow the character to experience their story directly – it will allow the reader to experience it directly, too, and that’s a more powerful reading experience.

Final thoughts

Point of view controls how readers experience characters’ sensory experiences and psychological states of being. It’s core to narrative writing, whether fiction or nonfiction. Once you learn how to use different kinds of POV, finding the right match for each story becomes easier and easier.

But if you feel uncertain about POV, don’t worry.

Get started with a limited point of view (first person or third-person limited), so you have some boundaries within which to experiment. And above all, play with the different kinds of POV. Free-write scenes in different narrative styles, so you can get a feel for how they work. The more you practice, the more comfortable you’ll feel when the time comes to apply the POV that is right for whatever great story idea you’ve come up with.

And don’t forget to have fun with it. Experimenting with POV can be one of the most delightful ways to transform an ordinary story into something extraordinary.